words by Adina Glickstein

♡♡♡

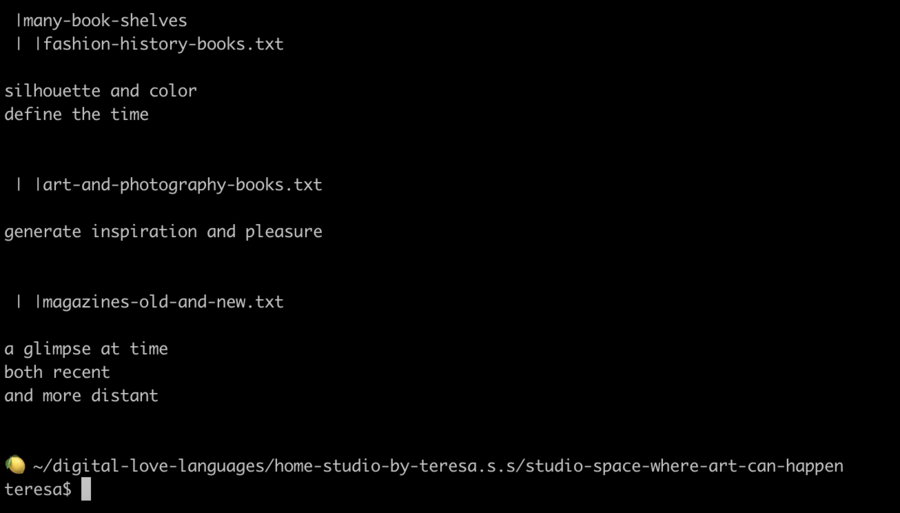

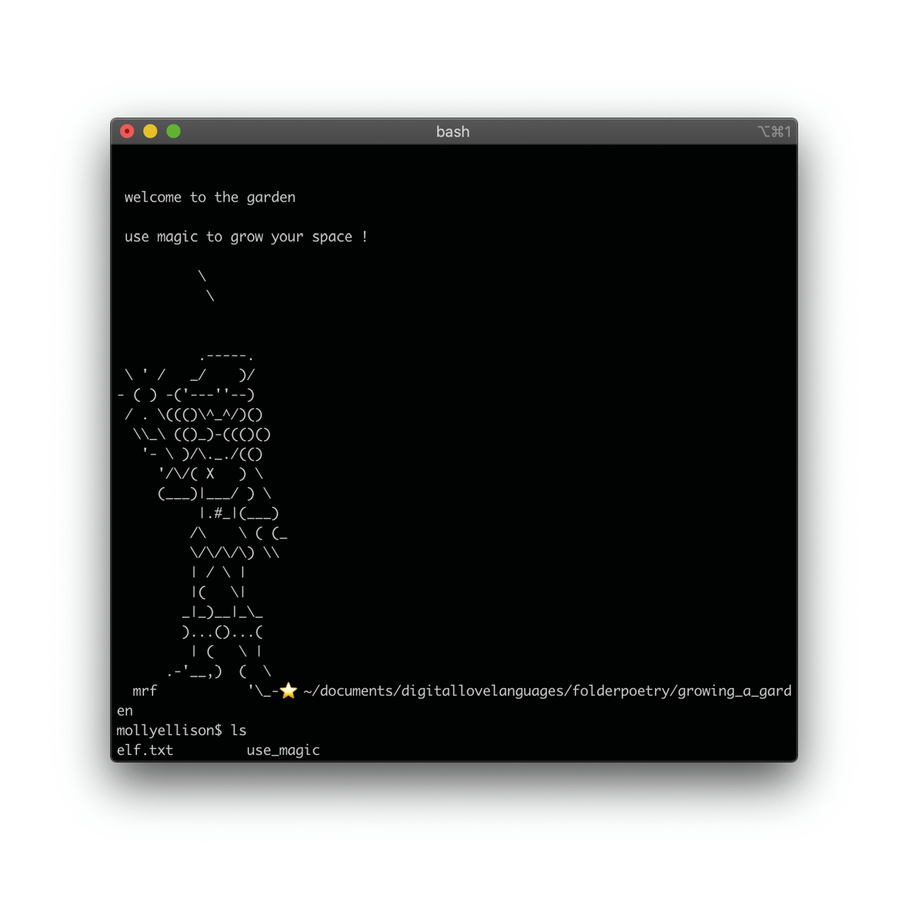

The first section of Digital Love Languages, which teaches bash scripting through Folder Poetry, includes an activity called Folders Anonymous. There is so much to say about Folder Poetry—about collapsing the distinction between “user” and “programmer”; about generating accessible ways of feeling “close to the metal”; about the ecstatic thrill of learning, in a day, how to use something as seemingly stoic as the command line in service of creative output—but Folders Anonymous keeps reverberating in my thoughts, so for brevity’s sake, it will serve as my starting point for some more general reflections on the possibility of digitally-mediated intimacy and the importance of refusing to take our interfaces at face-value, insisting instead on their status as partial and perspectival reflections of each of our diverse and specific brains and situations, our ways of moving through the world.

A digital trust-fall, Folders Anonymous split us off into breakout rooms to walk a classmate—still a near-stranger, though I can feel the softness of familiarity and ease opening up in these interactions more with each passing week—through our computer’s file organization system. First, Melanie showed us hers: full-screen windows stacked like a deck of cards, shuffled and navigated with the stroke of “cmd+tab.” Impossibly elegant! So much more efficient than all the clunky mousing-around I’m typically prone to, and a welcome invitation to rethink my own way of occupying screen-space. Even more profound was the sense of intimate vulnerability that comes from seeing another’s desktop—by default, the computer seems so generic and sterile, yet peeking at someone else’s feels like being privy to something intensely personal.

Already, a handful of weeks into Digital Love Languages, my frame of mind has been shifted towards the poetic. My first exposure to Folder Poetry came last January when I participated in Code Societies, and at that point, I began to wrap my head around this (at first, seemingly counterintuitive) sense of intimacy. In the intervening months between Code Societies and DLL, the depth of my engagement with my computer has intensified beyond what I thought possible: now, working from my hometown, my laptop is my primary portal to friends, lovers, employers, and fellow activists and organizers. Constantly, I think about Holly Herndon’s assertion that laptop music, far from being coldly disembodied, is deeply intertwined with our bodies and psyches. Speaking about her laptop, Herndon claims: “It is my instrument, memory, and window to most people that I love. It is my Home.”

Sharing our Finder windows with one another, we beamed each other into our Homes. The vulnerability of this gesture was certainly clear to me in Code Societies, but at that point, sitting next to one another in the SFPC classroom, its full depth was not expressed to me quite like it was this week in DLL. How can we build love—which is to say, how can we demonstrate trust—when we can’t even share a physical space? Inviting a stranger into your Home is certainly one way to begin.

Walking Anastazja through my desktop in Folders Anonymous, feeling simultaneously safe and silly as I struggled to explicate the file organization patterns that cease to make sense outside of my brain, initiated a sense of closeness and trust that I have repeatedly, over the course of the past few weeks, been amazed at the possibility of provoking by exclusively digital means. Intimacy without proximity: this maxim, originated by Donna Haraway in Staying With The Trouble, has become something of a mantra of late. Often, it’s deployed to hackneyed (if admittedly important) ends—but in learning to see the inherent poetry of our individualized, intimate methods of organizing and storing information, in sharing these creative patterns that oftentimes we did not even realize we were crafting, Haraway’s words resonate.

Another principle lifted from Haraway has guided my thinking throughout this exercise: the doctrine of “situated knowledge,” which reminds us that no knowing comes from nowhere—objectivity is a god-trick, and an increasingly untenable one at that. The graphical user interface, or GUI, proposes a sort of objectivity: navigating through Finder, it seems like I am accessing my computer from an omniscient seat of all-seeing capacity. Of course, this overhead perspective is an illusion, and its appearance of neutrality (as is true with so many facets of computing) is both false and potentially harmful.

The very metaphors that we often take for granted and which find their most literal expression in the GUI, “files” and “folders,” are inherited from the culture of white-collar office labor. Everest Pipkin has written on the implications of this metaphorical scheme at greater length than I have room to explore in this blog post, and I highly recommend their essay on the topic as an entry-point into reframing our relationship with the received assumptions of the “desktop.” In summary, it will suffice to point out that this skeuomorphic metaphor is selective and limiting, inheriting the racial and gendered biases of a real-life office environment and cementing them into our computer interfaces. All these inequities and power dynamics, obscured below the surface of a seemingly innocent metaphor that purports to let us operate as objective observers!

The notion of Folder Poetry serves as a wonderful way into thinking about our computers from the standpoints of “situated knowledge” and “partial perspective” that Haraway advocates. Navigating the command line, for instance, is necessarily a situated exercise: we walk through the file structure through a series of “ls” and “cd” commands, which remind us that we can only ever be in one place at one time. Even when the “treefile” command reveals a structure as if from above, it shows us a single individual’s customized folder environment, a reminder of the non-flatness, the non-sameness of each computer’s setup.

In this first exercise towards developing a more poetic relationship to our machines, I have been reminded that what I see when I look at my laptop is profoundly non-universal. Offering glimpses into our one-of-a-kind setups and habits, whether they’re the products of casual preference and intuition or architectural rigor, is an affirmation of situatedness: a way of inviting others into our Homes, taking accountability for the partiality of our perspectives, sharing poetry, and volunteering vulnerably. In digital communication and interpersonal interaction alike, these strike me as the ingredients of a relationship that is well-founded towards love.